A dive beneath the waters that floated the names Anhalonium/Lophophora lewinii

Let’s take a really deep breath first…

Will the real Lewinii please stand up?

Wait a minute, that’s not a real plant, that is Frankenstein!

The following is a summary of the reasons why Bruhn & Holmstedt (1974 Economic Botany, 28: 353-390) believed that Anhalonium williamsii was really Lophophora diffusa — and correspondingly that Anhalonium lewinii was really Lophophora williamsii

1. Altamirano 1905 had noted that peyote (referring to it as a single species, A. lewinii) was an item of commerce (12 cents for approximately 300 plants) and (among other areas) collected from the locality now known for the L. diffusa population in Querétaro. This area is the closest population to Mexico City and has probably been collected from many times. This shows that this locality was known and suggests that the plant was apparently an object of extensive trade. When Bruhn & Holmstedt collected L. diffusa they found it was still being called peyote. [They noted that J.N. Rose accompanied Altamirano on his trip to Querétaro and that a photograph of a plant which he collected had appeared in Safford’s 1915 work as representative of the ‘southern form’ of peyote.]

2. Several early chemical investigations of peyote (Bravo and also Robles & Gómez Robleda) were only able to isolate pellotine, having collected around Querétaro.

3. Pharmacological study by Jaensch, using dried peyote, found results in some of their volunteers which more closely resembled the action of pellotine than mescaline. (See more under L. williamsii.)

4. Heffter’s analysis showed A. lewinii to contain mescaline, anhalonine, anhalonidine and lophophorine; while A. williamsii only yielded pellotine for him, in Heffter 1898b. Notice that close to a decade elapses between the creation of Henning’s Anhalonium Lewinii and Heffter’s results. During that same decade is when both Coulter and Thompson were studying Anhalonium, and when Lophophora was borne (creating an era with a peculiar density of name changes including a strange inability of many authors to correctly assign the actual describers to the binomials.)

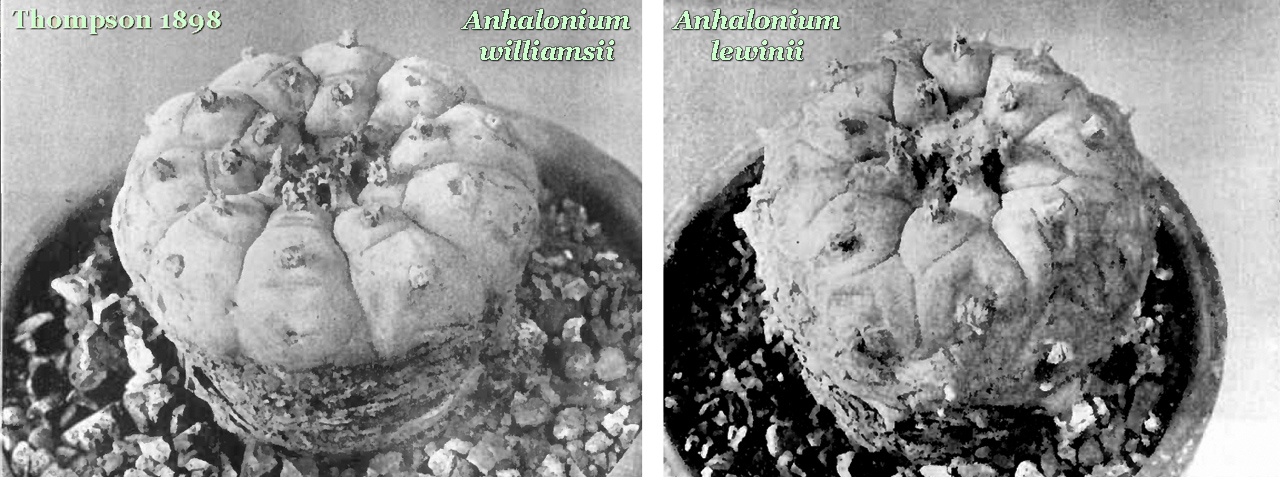

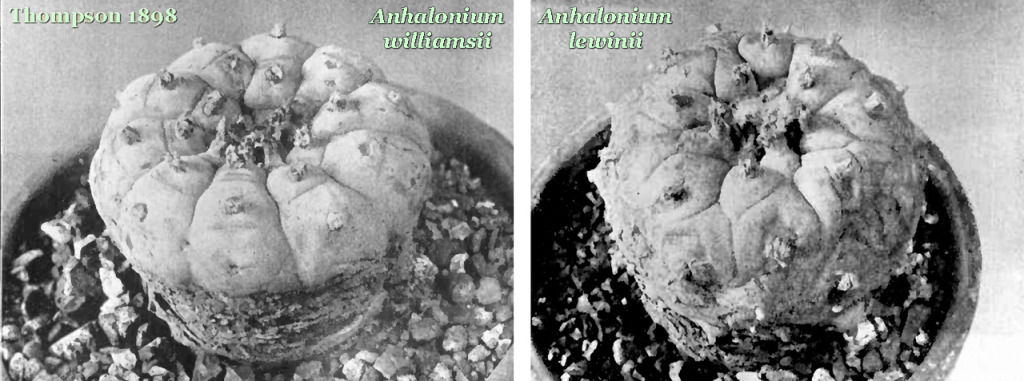

5. In Heffter’s first paper on peyote, his colored illustrations of A. williamsii and A. lewinii show more prominent ribs and tubercles on the latter and the same difference in coloration which has been noted by those who later described the two species of Lophophora as separate. (i.e. yellowish green for A. williamsii [and L. diffusa] and bluish green for A. lewinii [and L. williamsii].)

The plants in points 2 & 3 certainly appear to be Lophophora diffusa but a link for them representing “Lewinii“ and “Williamsii” is not included so it is actually a bit of a stretch to present this as supportive evidence. Especially as MOST peyote in that era would have been referred to as A. (or E.) williamsii with A. lewinii being regarded as a variant form only from 1880s onward.

The first three of the above are on shaky ground for consideration as evidence since what is being claimed actually all revolved around Heffter’s results, indicating to him there were two different plants involved, and the subsequent attempt to force fit his observation onto Lewin/Hennings’ pronouncement of there being two species. One of those it is crucial to recall was the rather frankensteinian “A. Lewinii” that had been created from a Parke-Davis peyote button.

Which makes those three points rather circular.

The mistaken assertion launched during that period, namely that “Lewinii” was the drug form used by Native Americans and was different from “Williamsii” seemed to assume a life of its own after that point and people almost scrambled to find and provide the drug plant.

The error began when Lewin and Hennings published their conclusion that Parke-Davis’ “buttons” came from a species other than Anhalonium/Echinocactus williamsii. This seems to have become additionally complicated and set in stone when the analytical results of Heffter, concerning what would eventually become Lophophora diffusa, were overlaid on the pronouncements of Lewin and Hennings. Prior to this it is important to keep in mind, both diffusa AND williamsii were considered to be A./E. williamsii. Once Anhalonium lewinii plants started entering horticulture, the fiction that A. williamsii really referred to what is now L. diffusa and not L. williamsii, became firmly established as if it was a fact rather than a limited case. Interestingly it only lasted until the 1920s.

Their error is mis-represented by Holmstedt & Bruhn as being the larger picture of the day despite it being the picture only in the far more restricted world of the chemists/pharmaceutists Heffer and Lewin and what few botanists & toxicologists were working with one or the other. It may be pertinent to note that Hennings was a mycologist rather than a botanist but fate placed his employment in the botanical garden at Berlin. The reality was that neither Heffter nor Lewin knew what they were talking about and made grevious errors of identification based on their analytical results. They can hardly be blamed as neither one was a botanist. It should not be made to appear more than it really was though. It needs to be recognized that those two workers (and the rest of medical and pharmaceutical science) were actually immersed in a state of confusion concerning peyote as a ceremonial drug plant. Those synonyms should therefore be understood to be a short-lived case of mistaken identity that has left persistent problems in nomenclature.

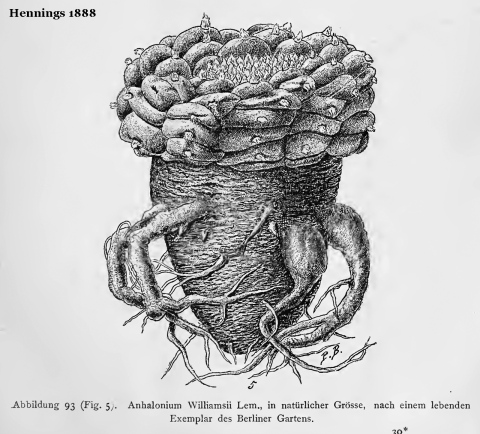

Most botanists held exactly the opposite view even in the 1890s and beyond. The antithesis of Heffter’s view however apparently did not percolate outward far enough to recreate A. Lewinii as a name successfully applied to L. diffusa until the early 1920s. (Notice also, that Paul Henning’s original drawing of Anhalonium williamsii in the collection at Berlin appears to be of a deeply-cut and then rerooted Lophophora williamsii rather than of Lophophora diffusa.)

- Boquillas, Mexico (cultivated)

- Presidio County

- Terrell County

Despite an initial acceptance of Hennings’ name, Schumann (and the core of the German cactus specialists of the day) rapidly became openly dismissive of the new species and Schumann proposed the concept of there being different chemical races within a single species in order to explain away Heffter’s results.

Once Lophophora diffusa entered into the picture as living plants of *A. Lewinii* there was no simple fixing of the pre-existing mess as the recognition of Lophophora diffusa provided a nice and neat answer to the identity of the “two” species. As long as no one wanted to dig too deeply and ask the question as to why TWO different A. Lewinii had appeared in European horticulture during those years.

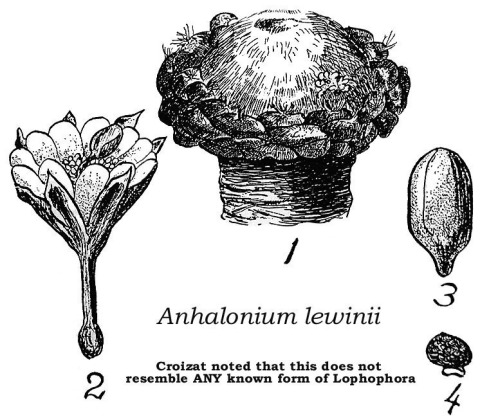

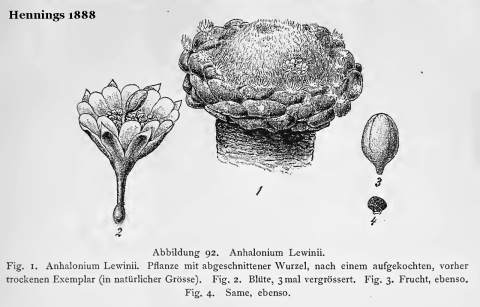

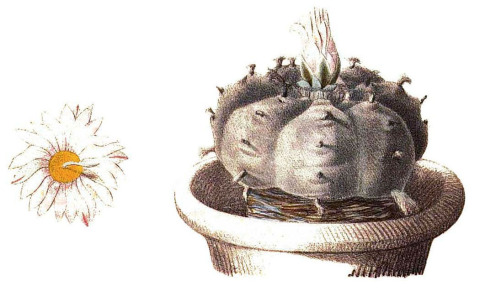

While we are still on the subject of Bruhn’s “The Anhalonium lewinii controversy” it is probably the appropriate point to diverge for a moment to reflect on the next image from Croizat who redrew Henning’s drawing of a peyote plant said to be A. lewinii. This image from Hennings is perhaps the single most important image on this page if it is understood correctly.

Based on this drawing, Croizat made the peculiar attempt to equate A. williamsii with Epithelantha micromeris that seems only worth mentioning as something odd which occurred and then move back to reflecting on this specimen as Lophophora. The reason that Croizat’s a proposal can be so simply dismissed out-of-hand is that not only does Hennings’ drawing lack any of the features that would be present on Epithelantha but it was clearly described as being produced from a peyote button that had been provided by Parke-Davis. The idea that a button of micromeris would have been prepared and then somehow become part of a lot of “mescal buttons” in the hands of Parke-Davis stretches beyond what is credible. Croizat’s proposal seems to entirely revolve around oft-repeated comments appearing in Lumholtz 1902 that Epithelantha micromeris had been used as a stimulant drug plant by the Tarahumar and was considered to be a form of peyote called mulato. There does not appear to be any additional evidence indicating its actual use as a drug plant (or that it existed as a trade item) in the accounts of later authors who cited only Lumholtz.

Readers might want to evaluate Croizat’s proposal by comparing that drawing with some actual Epithelantha micromeris plants growing in Presidio County.

- Epithelantha micromeris

- Epithelantha micromeris

- Epithelantha micromeris

Charles Henry Thompson 1898 had commented that Paul “Hennings, in his original description in Gartenflora, used a boiled-up dried specimen as the subject of his illustration” and referred to the results as being unsatisfactory.

The “specimen” of “Lewinii“ producing so much lasting controversy was actually a dried peyote button that Hennings had received from Lewin (who had obtained it from Parke-Davis). Depending on which account is accurate, either Lewin or Henning had boiled the dried crown in water attempting to rehydrate and hopefully reconstitute the original form of whatever plant which had created the button. (It is illuminating to recall that Parke-Davis did not even know that their drug came from a cactus plant when they set out to learn more by providing samples to multiple scientists in the USA and in Europe. They were simply pursuing John Brigg’s published account of a drug with a mind for its possible pharmaceutical development.)

The swollen mass which Hennings showed as resulting from that abused peyote button was the entire basis for his new “species” Anhalonium Lewinii. It was fueled with Parke-Davis’ assertion that *this* was the species of the plant used for drug purposes.

Similarly to Croizat, Thompson had found the central wooly mass in Hennings drawing to be confusing but, unlike Hennings and Croizat, Thompson wisely stopped at that point and did not engage in further conjecture.

I apparently am not so wise as Thompson.

This is an image of a peyote button from Schultes below followed by another of an apparently dead peyote plant in West Texas of a form that is similar to what Coulter examined as examples of Lewinii growing near the mouth of the Pecos River.

One wonders what either one might look like after being “boiled up” until swollen?

I would propose however, that if one views Hennings’ drawing not as representing a plant but as being just a “boiled up” peyote button created from a perfectly good species that was already recognized, a lot of the smoke in this historical account of botanical confusion can be made to vanish. Simply by understanding that what was mistakenly being declared by Hennings to be a novel species was actually an entirely fictional creation.

Almost incredibly, Anhalonium Lewinii was soon becoming known in Europe as living plants not just Hennings’ “boiled-up” peyote button. We humans are certainly an interesting species.

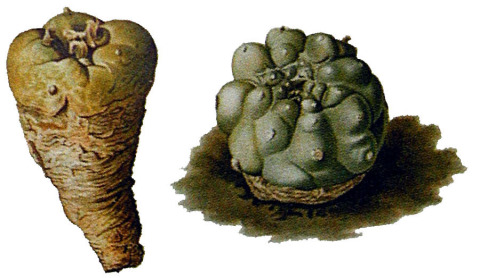

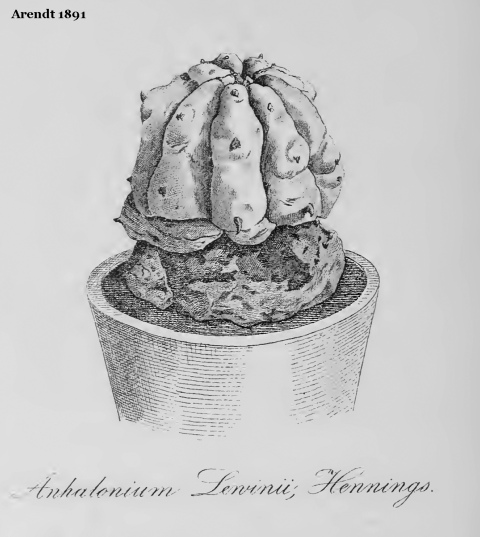

Paul Arendt 1891 produced a drawing that appears to be the first illustration of the new, ahem, species; including a description that clearly gives Anhalonium Lewinii‘s flower color as pink (“blassrosa“).

In all those cases, except obviously for Croizat & Hennings, the arguments presented would seem sound but its also clear that not all early workers agreed with each other what was lewinii was. Botanists ascribed a rose/pink color (sometimes noting white as well) to the flowers of both species following their initial appearance in Europe.

It was only because of the drug company Parke-Davis entering the picture when trying to learn an identity for a new crude drug they had acquired that the concept of Anhalonium Lewinii ever appeared. That is quite a fair evaulation as Lewinii could never have existed without that specific input accompanied by the idea being presented to Lewin that it was, for some reason, different from Anhalonium Williamsii. It seems peculiar that Brigg’s somehow would have missed peyote buttons as coming from a well-known botanical source since the indigenous use of Williamsii for ritual purposes was a fairly widely and well known phenomenon to *most* of the cactus botanists of the day. (Bender 1967 noted Briggs complained about difficulties in procuring a supply for Parke-Davis; these might suggest that Briggs encountered the same nature of source-protection that was mentioned by Johnson in 1909?) I’m still in the midst of collating the early opinions but what is presently clear is there was a lack the solidarity of opinions which is implied by what was selectively included in Bruhn & Holmstedt. I would propose that had Heffter not initially produced results indicating that two different plants existed, Henning’s new species would not have been accepted and would have rapidly been understood to be Anhalonium williamsii.

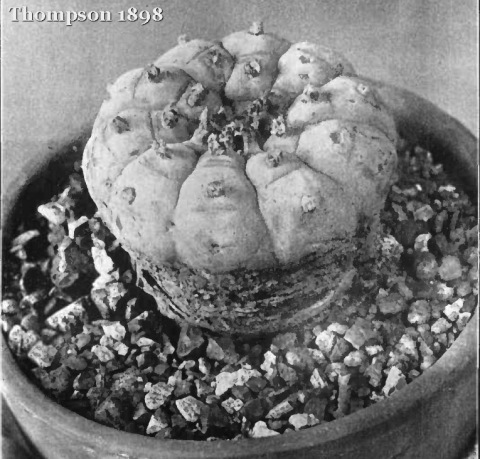

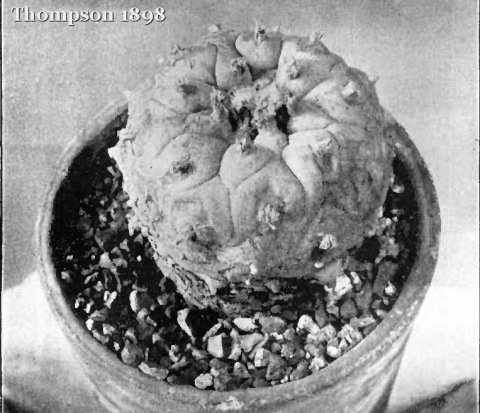

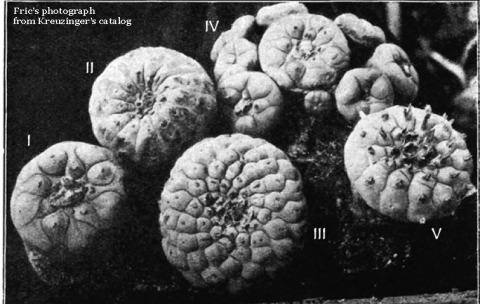

Bruhn & Holmstedt seem, for examples, to somehow have either missed or trivialized Thompson 1898 with his illuminating pair of images that are copied below, There is also the 1930s labelled version of Fric’s photograph of Lewinii (see at the beginning of this section) that is so strikingly similar to a typical L. diffusa. I would hate to imply those were omitted by Bruhn & Holmstedt due to not supporting their assertion? It certainly seems like a strange omission since Croizat makes direct reference to Thompson’s images.

In this case though, the point they missed sheds some interesting light on a possible identity that was jumped on quite early for “Lewinii“. (Recall that the early A. Lewinii all had pinkish flowers?) Take a look at these two images from Thompson and notice in particular the plant of “lewinii”. Just for now, try to resist making it yellowish in your mind and try to picture a grey body color. Keep in mind that these are those same two Anhalonium species according to the view of Thompson in 1898.

I’m also including images of wild L. williamsii growing in West Texas to perhaps provoke some thought.

Lophophora can be extremely variable in any population. We will come back to this elsewhere under “echinata” but it seemed appropriate to include these next few images following those from Thompson.

Let’s drop the color out of that image:

& can add some more in order to compare the ribbing:

- Presidio County

- Presidio County

- Presidio County

I’m not trying to present any of these images as being a typical form for any entire population but all are examples of what exists in nature. This is also a good example of how easy it might be to draw wrong conclusions when trying to extrapolate individuals in single photographs as representing entire populations. Despite that, I would suggest that these images bear a striking resemblence to Thompson’s Lophophora Lewinii. At least as much as does a diffusa.

Thompson’s “Lewinii” was growing at the Missouri Botanical Garden and was surely among the living specimens that Coulter used as his basis for Lophophora Williamsii var. Lewinii. (Thompson’s comments about intergradation suggests that he examined multiple specimens at the Missouri Botanical Garden prior to describing Lophophora williamsii.) Coulter based the varietal name on what was previously published in MfK but he adds comments on examining additional living specimens variously collected by a “Wm. Loyd of 1890”, from near the mouth of the Pecos River, plants provided by Mrs. Nickels in 1892 & 1893 and a specimen that had been collected on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande near Laredo in 1894. (At least some of that is for certain what Del Weniger referred to as L. williamsii var. echinata.)

Coulter’s specimens were growing in the Missouri Botanical Gardens in 1893 so it seems safe to think that it included the same material which Thompson 1888 had showed as a specimen of Lophophora Lewinii. Coulter favorably comparing this to peyote from near the mouth of the Pecos would seem to rule out Lophophora Lewinii sensu Thompson being a Lophophora diffusa.

Is “echinata sensu Weninger” what Coulter meant when referring to Lophophora williamsii var. Lewinii as: “A much more robust form, with more numerous (usually 13) and hence narrower and more sinuous ribs, and much more prominent tufts”?

- Chihuahua, Mexico (in cultivation)

- Chihuahua, Mexico (in cultivation)

- Chihuahua, Mexico (in cultivation)

These next three plants came from Val Verde County and were growing in two different research collections.

This could suggest that originally “Lewinii“, as a plant not the boiled peyote button, did refer to Lophophora williamsii and was possibly more specifically varietal for the West Texas and northern Mexican plants. (The most glaring problem with this being of course that since “Lewinii” a fictional creation of Hennings, all subsequent identifications were the result of people’s attempts to find, or create, that plant.)

Coulter summarized what fueled everyone’s persistent problems quite well when writing, “The extreme specific and varietal forms seem worthy of specific distinction, but abundant growing material in Mo. Bot. Gard. showed such complete intergradation that a specific line of separation was found to be impossible.”

A new name is needed for this form/variety/subspecies as Weniger’s application of “echinata” appears to be wrongly and confusedly applied, and “lewinii” is also hopelessly compromised by prior confused applications. While recognizing “echinata” needs a replacement, for now I’ll continue to perpetuate “echinata” in tribute to Del Weniger’s contributions. Let me know when there is a new name and I’ll gladly start using it.

Let’s get back to Anhalonium/Lophophora Lewinii, the plant. There is one major problem with this name that negates whatever follows its appearance. That is the simple fact that the name refers to a plant that never actually existed. Sure people like Thompson tried to make sense of it based on examples they could *find*, and a couple of different plants seem to have entered horticulture under that name at one point or another, but the reality is a little more stark and impoverished.

The peyote buttons which Briggs organized to reach Parke-Davis and which Parke-Davis sent to multiple scientists worldwise were most certainly dried Lophophora williamsii. It is possible they came from West Texas plants but it does not seem likely based on the typically small populations which occur in the more extreme parts of Lophophora‘s range. When those dried L. williamsii reached Lewin, and then after being subjected to a good boiling by Hennings, the surely misshapen and swollen result became Anhalonium Lewinii. As Anhalonium Lewinii never actually existed, all subsquent plants arising with that name, first with pink and then later with yellow flowers, are the result of well-intentioned but erroneous attempts to respect the belief they held in the writings and thoughts from other authorities. A blind respect for those published accounts of their peers has recurrently caused problems in the story of Lophophora nomenclature.

Heffter’s analysis and near discovery of Lophophora diffusa obscured this by helping solidify A. Lewinii into a sort of fictional pseudoentity by assuming (as did Bruhn & Holmstedt) that if A. Lewinii was the drug plant (now L. williamsii) then it must mean that A. Williamsii was his pellotine plant, namely what is now L. diffusa.

It is fascinating how fast people found living examples of it to bring it into horticultural reality but it is perhaps important to recall cactus collection has long been the sport of kings and the idle rich so many well organized and highly-motivated professional cactus collectors have existed for several centuries.

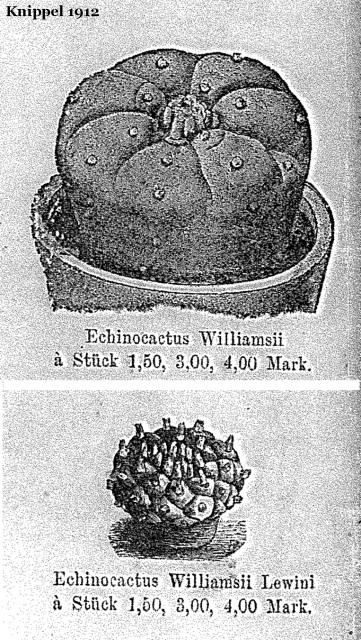

Keep in mind that Hennings published his new species name in 1888. 1891 & 1894 saw the first two published illustrations of Anhalonium Lewinii appear; followed by an actual photograph in 1898. In 1912, both “species” were available as offerings in the Knippel catalog.

The recognition of multiple forms or species, with a lack of agreement on the actual details, lead to there being a parallel Lophophora diffusa due to some people experiencing the same sort of problems that others have had with williamsii.

In 1929, the Friedrich Adolph Haage, Jr. catalog listed

“Lophophora Lewinii Hen” (I would assume that by 1929 Haage’s L. Lewinii had yellow flowers?)

Lophophora ritteri Böd “(prices on application)”

Lophophora williamsii Lem.

Lophophora ” var. luteiflora”

While yellow flowers came to predominate what was regarded to be L. Lewinii in European (and other) horticulture, the picture could not neatly segregate along the lines of pink versus yellow flowers as the two correspondingly different lineages, including the early pink flowered L. lewinii, obviously continued to exist in European collections.

In John Borg’s 1937 Cacti, (Lophophora entry is pages 263-264):

Lophophora Williamsii flowers: “pink or pale pink or almost white with a darker midrib.”

Lophophora Lewinii “Often considered as a variety of the preceeding. Different chiefly on account of the plant being larger, with more numerous and more pronounced but narrower ribs, with more prominent tubercles and larger tufts of wool. The flowers are pale pink or very pale yellow with far less tendency to sprout.

Lophophora Ziegleri Werd. Mexico. Still very rare in cultivation. Stem mostly solitary, very galucous and very smooth, with about 8 ribs just marked out by lines or slight furrows. Tubercles very low, with small tufts of white or whitish matted wool. The stem is more rounded, and hardly depressed at the centre, and the flowers are pale yellow.”

This persisted even after Bravo cleanly defined L. diffusa. The resulting synonyms that had appeared during those early years can still be encountered in horticulture.

Some history for the names Lewinii and Williamsii

Let’s look at some more of the older botanical descriptions and images of peyote with a mind for evaluating what people of the day actually regarded to be Williamsii and later as Lewinii.

The first botanical description of Peyote lacked an illustration and was in Charles Lemaire 1845 Allgemeine Gartenzeitung, 13 (45): 385-286 (I won’t include Hernandez despite that being much earlier as it lacks a mention of the flower color).

It was actually written by Friedrich Otto & Albert Dietrich.

The flower color was given as “roseis“.

The first appearance of an illustration of Echinocactus Williamsii was in Hooker 1847 Curtis’ Botanical Magazine; plate 4269. In this description the flowers were said to be “white, externally tipped with pale green, and having a rose-coloured line down the centre“.

The second appearance of an illustration was Pfieffer (and Otto) 1846-1850 Bluhende Cacteen Volume 2; plate 21. The flower color of Echinocactus Williamsii was said to be “roseis“.

In Salm-Dyck 1850 (ennumerating what was in his collection in 1849), Link & Otto describe the flower color of Echinocereus Williamsii as “pallide roseis” with a “rubra” midstripe on the petals.

In Förster 1888: the name Anhalonium Williamsii appears described as having a flower color of “blassrosa, aussen mit einer dunkleren Mittelinie “.

In 1888, A. Lewinii is borne from a “boiled up” dried peyote button (of A. Williamsii) and declared to be a new species by Paul Hennings.

As was mentioned (with illustrations) earlier, live plants of “Lewinii” that had begun appearing in Europe served as the basis for a published illustration by Paul Arendt in 1891 and another by Karl Schuman in 1894. Charles Thompson added a photograph to the literature in 1898.

Coulter 1892 gives the flower color of Lophophora williamsii as “whitish to rose” but does not mention a flower color for his “var. Lewinii“. He does indicate that he thinks Thompson’s Lophophora Lewinii at the Missouri Botanical Gardens is synonymous with plants he examined from near the mouth of the Pecos River.

Both species also became available for sale within not many years. I’m only guessing that Knippel’s Echinocactus lewinii in the drawing below had pinkish flowers and was NOT a Lophophora diffusa.

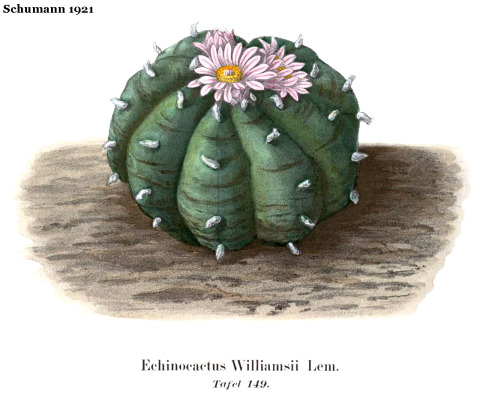

In Schumann 1921 Echinocactus williamsii is shown with pale pinkish flowers possessing a darker pink midstripe.

Schumann dismisses all other species (and never embraced either Anhalonium or Lophophora).

It appears to be in Isaac Ochoterena 1922 Las Cactacees de Mexico where a yellow flower first became attached to the name “Lewinii” but I am still digging through that rather horrific mass of verbage that is regarded to be the early peyote literature. (The Lophophora entry is pp 96-100.)

At any rate, Lophophora Williamsii was said by Ochoterena to have white or rose flowers (“blanca o color de rosa“); Lophophora Lewinii to have yellow flowers (“flor de color amarillo“). Pertinent to our analysis, he includes Thompson’s pair of potted peyote images as his examples for Lophophora Lewinii and Lophophora Williamsii rather than generating his own examples based on wild Mexican plants.

Frič (in Kreuzinger 1935), was no doubt influenced by this as he similarly gives Lophophora lewinii‘s flower color as “blaßgelb” and, in his label on an image of what appears to be L. fričii, listed L. williamsii as having “blaßrosa” flowers.

I “Lewinii (Hennings) blaßgelb Blüten”.

(In Frič 1924 this was originally designated as sp. lutea Fric and was noted to be from Queretaro.)

In Backeberg 1961, this same image appears renamed as Lophophora lutea (Rouh.) Backeberg.II “texana” In Backeberg 1961 this is L. lutea texana (Fric ex Krzgr.) Backbg.

III “Williamsii (Lem.) blaßrosa Blüten”

(In its earlier appearance this was Anhalonium sp. fl. rosea Frič – Frič 1924 & 1925. It was said to have come from Coahuila.)

In Backeberg 1961 this became “L. williamsii v decipiens Croiz (Altersform?)”IV “caespitosa (San Luis)”

V “jourdaniana (syn. violaciflora) violetrosa Blüten”

(In 1924, Frič gave this as A. Lewinii from Chihuahua.)

Backeberg 1961 preserved this as jourdaniana.

We have already noted earlier that Borg 1937 was continuing to recognize pink as a potential flower color of L. Lewinii.

W. Taylor Marshall & Thor Methven Bock 1941 Cactacae 138

“Lophophora Lewinii (Hennings) Thompson, while described in 1888, has recently been introduced in the trade as a species.

The color is a yellowish-green and the tubercles are fewer and larger than in L. Williamsii and the tufts of wool not so pronounced; flowers white to cream.

Lophophora Tiegleri Werd., seems to be identical with the preceeding species of variety.”

L. Chavier (1953) Cactus France 38: 255, under:

“Lophophora williamsii et Tiegleri” gives as synonyms: Lewinii, Tiegleri, Ziegleri and says they have a very pale yellow flower.

The photograph shown is clearly diffusa despite being too poor to reproduce.

P. Fournier (1954) Les Cactées et les Plantes Grasses

Gave the body and flower colors as yellow for L. Lewinii with the flowers for L. williamsii as being pale rose with darker pink midstripes.